Daniel Cohen is an Israeli conductor who has been the General Music Director1 of the Staatstheater Darmstadt since 2018, a job he combines with an international conducting career. He was previously Kapellmeister2 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin and also conducted at the Staatsoper Berlin, as well as working frequently with the Israeli Opera.

Daniel was an assistant to Pierre Boulez at the Lucerne Festival Academy and pursues his passion of contemporary music today as Artistic Director of the Gropius Ensemble. As a violinist, Daniel was a long-term member of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, where he was also Assistant Conductor to Daniel Barenboim.

You can find the German version of this interview here.

The passion to communicate something from me to you is the foundation of our profession.

DT: We’ll start with a quick-fire round. If you could have a meal with one person in history, who would you choose?

DC: Verdi. I think he’s the only good bloke from most of the composers.

DT: Give me a song that would get you on the dance floor.

DC: I don’t think it’s been written yet!

DT: If you weren’t a musician, what would you be?

DC: A gardener.

DT: Do you have a favourite opera?

DC: Wozzeck [by Alban Berg]. I conducted it once quite a while ago without rehearsal, and I can’t wait to do it again.

DT: Favourite composer?

DC: Mozart.

DT: Could you describe your Hot Toddy (or other beverage) in three words?

DC: At the moment I’m having a non-alcoholic drink with half a lemon together with its juice, lemon blossoms, clove, cinnamon sticks, honey, and fresh ginger. It’s very elaborate, a masterpiece!

DT: You studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, and after studying violin there, you entered the conducting course when it was run by Colin Metters, with Visiting Professor George Hurst. Can you tell me a bit about your time there?

DC: I first went there when I was about to have my eighteenth birthday. I saw they were having auditions, and asked my mother whether they would consider covering my trip to London [from Israel] as a birthday present, so that I could go and audition.

It was really an excuse to see London, which I had always heard about because my grandmother used to read me poems by T.S. Eliot as bedtime stories, and I wanted to see this ‘yellow fog’ that he talks about in his poems. I got accepted to do violin and conducting, so after a year of violin I began the conducting course, which lasted for three years.

The conducting course was very interesting. For the grounding of the physical language, Colin Metters was very good – extremely pedantic. He had a way of teaching which involved making a disconnect between your expression and technique, so that you could use your technique to dictate your expression, and not vice versa, which is a brilliant idea.

I found it extremely hard; it’s a little against my character to separate things and to think about a musical phrase while putting aside my musical impulse. But I can see the value of it. It took a lot of time to find a language of communication. He was teaching more the metaphysics of conducting: what happens inside the gesture and how you control it, the size and speed.

Then we had George Hurst, who was a phenomenal musician, and I learned a lot from watching him. He had a way of pacing the music, a way of turning a corner, that was very English, almost like Thomas Beecham used to have, which was really masterful: very old-school, very elegant. He was also very explosive and had a real temper, but his way of getting the students to focus on the merit of the score and not on what you felt like doing was a very good lesson for life.

I remember when we did Brahms’ 3rd Symphony with him with two pianos, and he spoke a little bit about the beginning. Someone got up and started to conduct the first two lines and Hurst started screaming at him, shouting that the student had already lost the battle and that the entire piece was lost because of what he had done! Hurst worked himself into a tantrum, and then he took the baton from the student, went on the podium, and proceeded to conduct the entire symphony.

It was the best Brahms 3 I’ve ever heard. Just superb, especially the pacing of the third movement, which was unbelievable, just unforgettable. He’d always visit for a week, and we’d always take a bet, who was going to be on the ropes when he’d finished, because every visit there was one victim!

Colin Davis also taught masterclasses once a term, which was a huge inspiration. He wasn’t particularly interested in teaching conducting, but his music-making was really inspirational. His thing when working with conductors was that you mustn’t use the stick as a stick. You can use it as a dagger or a feather, but you must paint with it or express something with it.

Barenboim is a meticulous thinker, and because of this, it’s quite easy to follow him into an idea.

DT: Were you already playing in the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra at that time? Can you tell me more about your experiences playing violin with them?

DC: Yes, I think I started around the same time, around 2003. It was a family. We grew up together and we were all more or less the same age, though from very different backgrounds. Today it’s funny to think about it, but then it was the first time that I met anyone from the Arab world that wasn’t living in Israel. My partner grew up in Jerusalem, and for her it was a lot less segregated than where I grew up, but where I was, the only friend I had of Palestinian descent was living in Nazareth, and he also played in the orchestra.

We studied together at the Academy in Tel Aviv and played chamber music together. I’d never met anyone from Syria, or Lebanon, or Ramallah, or anywhere like this, so it was quite a shock to get to know people, and the most interesting thing was that we lived and worked together very hard for six or seven weeks, often travelling halfway around the globe for tours to South America or Europe. We went everywhere together.

DT: Were there any musical projects that stick out in your memory as ones you particularly enjoyed?

DC: Sure. We did so much. We started with sectional rehearsals for a whole week. The entire summer was [Beethoven’s] Eroica and the Unfinished [Symphony, by Schubert]. The first year was extraordinary. With time the orchestra became more and more professional, but at the beginning it was a very homogeneous group. We had people who went on to play in the Berlin Philharmonic and Bayerische Staatsoper [in Munich], but we also had people from both sides who were either students or advanced amateurs.

The project of playing in Ramallah sticks out to me, which today is totally unthinkable and even then was out of the box. There’s a very interesting documentary about the trip that we took because it was the end of the tour, and the orchestra had to split. We couldn’t all travel together of course because the Israelis had to switch to diplomatic passports. Israelis are not allowed to go there normally, and all the Arabs couldn’t come through Israel because they are not allowed to have the stamp of Israel, so they had to go through Jordan and change to a diplomatic passport there. It was quite a thing. Then we played Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and it was an unforgettable occasion.

DT: Is that where you first met Daniel Barenboim?

DC: Yes. He came and rehearsed two weeks on this programme, three sessions a day, so he really rehearsed every harmony change, every fingering, every bow, speed and vibrato speed and everything. By the time we came to the concert, everybody knew the piece sideways and knew everybody else’s part. When we went on tour and did the balance check we even started playing the symphony on our own without him, because we knew it so well. It was a really magical experience that you don’t get in any other setting.

I remember playing [Wagner’s] Tristan and Isolde because it started with the Israeli brass players. They went to Barenboim and said ‘we never get a chance to play this because we are not allowed to play it in Israel. You are such an authority on this repertoire. Could we maybe think of doing one rehearsal and just reading something?’ And he said ‘if you get the consensus of the entire orchestra to do it, then for sure.’

It erupted like you wouldn’t believe. There were fights and screaming. One of the cellists said that her grandmother, who was a survivor from Auschwitz, spoke to her on the phone and said ‘If you play this, then when you come back home, you are no longer my granddaughter’. So it was not an easy decision to make. In the end, it was decided you didn’t have to take part, but there was enough of a majority to enable us to do a rehearsal. Barenboim said the immortal line ‘ok let’s take the morning off and start at 11am’.

He started at the piano, three hours without any notes, talking about Wagner, his life story, why his music matters, why his music is controversial, the historical context of everything, all the time giving musical examples. After three hours we started playing the prelude to Tristan. Barenboim worked maybe 25 minutes on the first two bars. It was really exceptional. Then we had a break and decided we were going to have a run-through as a conclusion for the day. The soprano Waltraud Meier, who was there because she was singing Beethoven’s 9 with us on tour, was listening, and she just started singing with us!

DT: Barenboim went on to become a mentor to you after that. What would you say are the main things that he’s brought to you as a musician?

DC: I think with him, it is perhaps easier to give a concrete answer than with a lot of other teachers, because the reason why he is such a good teacher, as well as a great conductor, is that he has a unique ability to explain verbally to the orchestra and his students what he means; how he builds his sound, how he builds the phrasing, how he builds the structure of the movement.

Of course he could fill a book and still not finish everything, but with the violin playing he had a lot to teach me about the speed of the bow, the intensity of the bow, fingering, orchestral fingering, where to play on which string for what effect. Balancing was a great thing for him; even today when I work on intonation I use what he taught us, because without a good balance the music always sounds out of tune.

Barenboim is a meticulous thinker, and because of this, it’s quite easy to follow him into an idea. You can see this in the books he has published; they are almost like a handbook. They give you an idea that is something concrete to work with, which is not often the case with music teachers.

For a lot of other teachers it has to do with inspiration, with mimicking, being almost a metaphysical guide, like it was with Colin Davis. Davis would say things during the Eroica like, ‘you really have to take it seriously. It might not be your funeral today but one day it will be, so you have to really imagine’.

So it had a lot to do with inspiration and imagery, which was really interesting and helpful, but it wasn’t something you could really quantify or verbalize. With Barenboim a lot of the time we would do a very complex piece and he would just take it apart to make everything understandable.

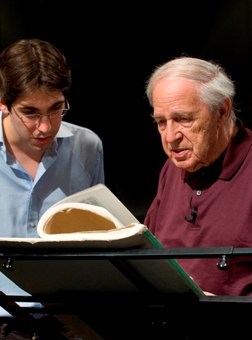

Photo by Priska Ketterer.

When I conducted [for Boulez] for the first time I just about managed to finish the section…and the orchestra all hit the bows on the music stand to say ‘well done, you survived it’. Boulez just laughed, looked at me and said ‘well, yes very good, but you know it’s not exactly precise’.

DT: Another important figure you assisted as a conductor was Pierre Boulez, who you worked with at the Lucerne Festival. What was he like to work with?

DC: You know, I don’t know if my impression of him is wrong, or that I saw a different person from the stories. Perhaps because he was already very old, he was different. He had very dry communication skills in front of the orchestra. He was definitely not an explosion of emotions, but the personal work with him was always very warm. He was a very funny person to us, his assistants, always very charming, but with the orchestra he could be quite harsh.

The work itself was not in fact very different from the work with Barenboim. He had a lot to do with texture, getting the texture to a point where you can really capture it in your ears in one unit that consists of many elements. That’s why when he used to conduct Debussy or Berg it sounded so interesting, because you had the feeling that you could really follow each voice. I didn’t get the feeling that he was so preoccupied with sound, in contrast to Barenboim, for whom the actual tone production is the most important.

With Boulez, I felt that that the starting point was making the score intelligible. It was interesting working with Boulez on his own music, because one got the feeling that because of the physical way that he conducted, he was quite precise.

However, the amount of rubato that he did in his pieces was extraordinary, overwhelming. For instance, if you listen to his recording of Notations, you will see that he contradicts his score in almost every bar. It is as free an interpretation as any top Italian conductor conducting Puccini. When there is an explosion of colour or resonance, he would always give it time to reverberate and he would never charge forward just because it’s an 11/8 bar. Instead, he would take time.

The first time I worked with Boulez was on his piece Répons, which was very tricky. There’s a big motoric section, and it’s not written in a metre, so it’s just a collection of short notes. You just have a beat and you have to elongate and shorten the beat according to the number of notes, which was a good three weeks of study to conduct those three minutes of music.

When I conducted the first time I just about managed to finish the section, like a bullfighter clinging on at the end of a rodeo, and the orchestra all hit the bows on the music stand to say ‘well done, you survived it’. Boulez just laughed, looked at me and said ‘well, yes very good, but you know it’s not exactly precise’.

Later, when that bit was over and the bells section started, he said ‘why are you conducting this like it’s new music?’ I was very rigorously keeping the rhythm, but he said, ‘you have to let the sound reverberate and listen that it’s really finished doing acoustically what it needs to do. It doesn’t have to be rigorous: it’s a structure.’

A good collaboration is when the conductor is working with their eyes as a spectator and the director is working with their ears. It is a process of building together.

DT: When did you begin working in opera?

DC: Opera was a very late addition to my life. I grew up playing the violin and as a symphonist. There was a situation in the Israeli opera when the music director left and suddenly there was a big vacuum. The person who was in charge called me and asked if I wanted to assist and conduct those shows that were now free. Which young conductor would say no to sixteen Rigolettos or something like this? But truth be told I started doing a lot of opera far too early and before I was actually able to do it. You can learn on the job and some of it was better, some of it was not.

DT: How do you see your role when you are conducting an opera?

I think it’s very different between opera and symphonic music. In your symphonic role you have the responsibility to facilitate the orchestral piece, which is autonomous. In opera the music is a part of the things that are going on, so what the orchestral players and what the singers need from you is quite different. It’s not that [conducting opera] is less expressive, it’s more to do with the fact that they need a different temperature from you.

When you are conducting the first symphony of Mahler and the orchestra is whipping up a storm with you, and you are together and focused on doing something, it’s a different temperature of expression than when you are down in the pit and the singer is standing on their head, hanging from the ceiling and having to come in with a scream or a soft note or whatever. They’re the ones that actually have to do it, and you’re the one that has to facilitate it. There’s a different temperature of collaboration.

A lot of your job is to bring it together visually with your language, your gesture, your expression, but also to make sure that you practically give what the singer and orchestra needs to know where to play, how to play, with which articulation, dynamic, all of that.

DT: When you have a new score of an opera for the first time, how do you go about preparing it?

DC: I’m a little bit disadvantaged in opera in the sense that my Italian is reasonably OK, my German is not brilliant, and my French is basically non-existent. Therefore I usually need a little more time than the average conductor to study the libretto. If I can and have enough time, I always try to study the libretto without the music, so I will take a good translation, where every word is translated, study the meaning and poetry, learn how to pronounce it and then study the vocal lines by singing them.

I’m quite a horrible singer, but I find if I can sing it then I can always accompany it, because I learn what is needed or what the challenges are in phrasing or breathing. Everything after that falls into place, of course more so in the bel canto Italian repertoire than in Wagner, because in Wagner it’s a little bit different. When I study Wagner, I study the libretto and then I have to study everything from all the angles at once.

DT: What opera repertoire are you most comfortable in?

DC: I’ve done Mozart the most, which I always find a very joyous experience.

DT: What do you look for when you’re casting a singer?

DC: I don’t know, but I know it when I see it! Sometimes someone comes on stage and they sing, and we all look at each other and go ‘yes that’s it’. When that happens, then you know. When it doesn’t happen, then you try and go for the best person that you have. Sometimes you take a risk and you think ‘okay this is not 100% secure but the whole package is worth the risk’. And sometimes you think it’s not really the whole package but it’s very secure and perhaps for this role, that’s more important.

I wouldn’t take someone who sings well but is boring on stage. But of course because of the way I view the world, then music is my priority. For the theatre people, the stage presence is their priority, so by the nature of things, when we sit in a panel, which is always the case, we balance each other out.

DT: What do you look for in a director?

DC: Collaboration. The thing that I don’t like is to feel that we are coming to the first rehearsal so that we can implement the fantasy of the director. When you start to work, it is building an interpretation together and the direction influences the music and vice versa. Then it’s an interesting process.

It doesn’t really make a difference to me what type of staging it is. A good collaboration is when the conductor is working with their eyes as a spectator and the director is working with their ears. It is a process of building together. This is why working with Andrea Moses [on Wagner’s Lohengrin, in Darmstadt] was so good: very often the way that I would do a phrase would trigger something in her direction or the actor triggered something in my interpretation, so it was really a joyous experience.

DT: What would be your advice for a young conductor wanting to work in opera?

DC: Study languages. Don’t make the mistake I did and think you can do it later. Study languages yesterday!

DT: Where do you see opera in 100 years? Where’s it going to be and what’s it going to look like?

DC: At the moment, I cannot tell you where opera is going to be in 100 days, because the world around us is changing faster than we anticipated [due to the Coronavirus pandemic]. At the moment the situation in Germany is much better than many other places, and the priority art has in Germany is considerably better than in other places. The place that culture takes in German life is really second to none. I hope that eventually when things go back to normal and we can play to a large number of people, that everything can keep going.

I don’t think opera needs to change too much – it is a combination of art forms that creates something that is bigger than the sum of its parts. When you think about this definition of opera, it’s not really changed from Monteverdi to Donizetti, from Wagner to Thomas Ades. The passion to communicate something from me to you is the foundation of our profession.

Thank you to Daniel Cohen for his fascinating insights and openness in the discussion this week. You can learn more about Daniel, including details of his upcoming performances at his website here. As always, please leave comments below to let us know what you thought and if you have any suggestions for future interviews!

Notes and Links

- A General Music Direktor (Generalmusikdirektor or GMD) is the musical head of a theatre in the German opera system. They are a conductor who is in charge of musical programming and planning, the artistic output of the music staff and singers, and they have the first say on what they will conduct in a season. They also have a strong influence on any casting decisions taken by the theatre.

- A Kapellmeister is a conductor who is one step down from the GMD. They usually have the second choice of performances to conduct after the GMD. Often there is a first and second Kapellmeister in a theatre.

- The conducting course at the Royal Academy of Music is now run by Sian Edwards. You can read more about the course at their website here.

- The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra (link here) was founded in 1999 by Daniel Barenboim and Edward Said, and its aim is to promote understanding between Israelis and Palestinians and pave the way for a peaceful and fair solution of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

- The Lucerne Festival (link here) was founded in 1938 and invites top musicians from around the world every year to an idyllic setting nestled on Lake Lucerne, in the heart of Switzerland. Unfortunately the 2020 festival has been cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.