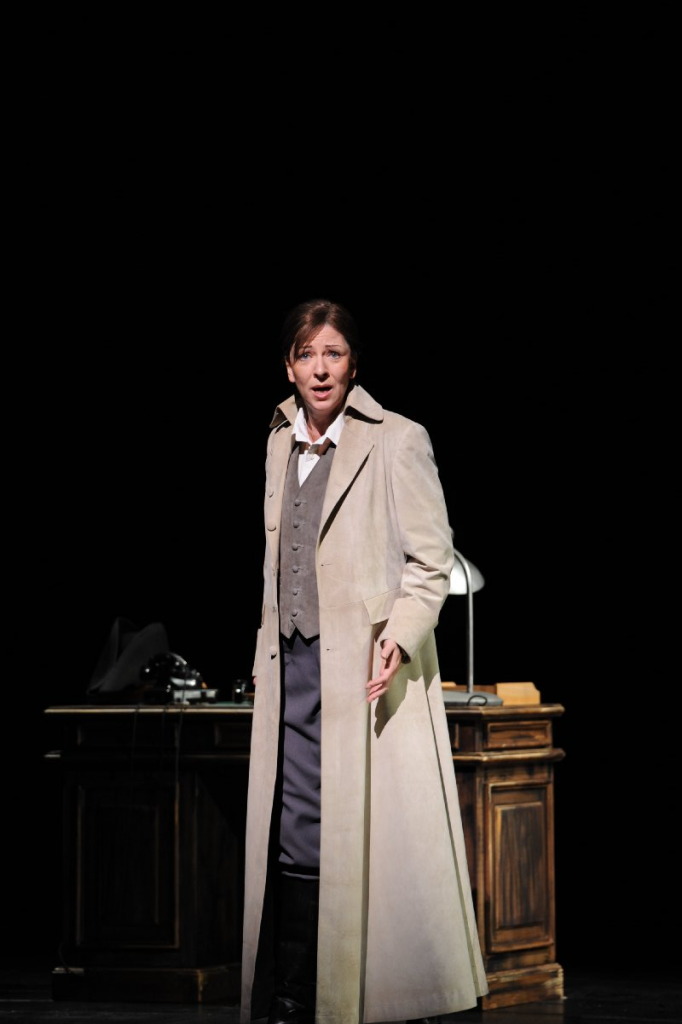

Dramatic soprano Katrin Gerstenberger joined the ensemble of Staatstheater Darmstadt in 1993, and in 2014 was honoured with the title of Kammersängerin. She was born in Halle in former East Germany (GDR) where she studied singing and sport, and in 1990 she won first prize at the Nationalen Opernsängerwettbewerb. She than began her first engagement in Gera, playing Azucena in Il trovatore. In 2004 she became a dramatic soprano and has since sung roles such as Antigonae (Orff), Turandot, Leonore (Fidelio) und Brünnhilde in Wagner’s complete Ring cycle.

This interview was done in German. For the original German version, please click here.

That’s the exciting thing about our profession, that you can do anything – from opera to operetta to musical – and through that you can find out what you are capable of. You can let all the ideas you have come up with come out on stage. I like that.

If you had not chosen opera, which profession would you have liked to pursue?

I would have done something either with garden and landscape design, or something with animals.

If you could have dinner with a famous person from history, who would you choose?

I have always wanted to meet Sir Peter Ustinov. He played Nero very, very early on and I thought he was a great stage actor. If they have to still be alive, then I would like to take Sean Connery. I think he has become better with age! As a guy, as an actor, everything.

Do you have a favourite instrument?

I think the human voice is a great instrument in itself, not only for opera, but when you think about the different kinds of music you can make with the human voice: starting with throat singing from Mongolia or African singing, for example. It is generally impressive what sounds the human voice produces and what music you can make with it, even just beat-boxing or pure speech. That’s my favourite instrument.

What is your favourite opera?

To sing: Götterdämmerung. I can only listen to an opera in peace where I definitely have nothing to sing: La Bohème for example!

Do you have a favourite composer?

Wagner. Lohengrin is the only Wagner opera I haven’t done. I’ve already done all of the others here in Darmstadt.

As far as security and practicing the profession were concerned, [the GDR] was incomparable with today.

You were born and raised in Halle in the former GDR. What was it like to be a musician and artist back then?

As far as security and practicing the profession were concerned, it was incomparable with today. The small GDR had 42 theatres (categorised as A, B and C theatres) and four colleges and universities, which only trained as many musicians as were able to get a job. Our jobs were called ‘Grabsteinverpflichtung’ [lit. gravestone engagement]. If you had an engagement and you didn’t misbehave politically or artistically, you were sure to have the job until retirement. I started in 1990 in Gera and I could still be there if I had wanted to be.

In GDR times it was quite normal that you could develop in a theatre. I experienced the development of young singers in the ensemble during my studies and three years after reunification. It worked very well. A maximum of 20 soloists were trained per year and about 60 to 80 choir singers. They all got a job.

Did you have to audition for the jobs?

Yes, it was called DTO (Direction for Theatre and Orchestra), and it was a great invention. There was a market like a big stock exchange in Weimar in the graduation year in February. The jury was made up of singing professors, conductors, opera directors, artistic directors and managers, i.e. people who knew something about music theatre. They came for example from the Berlin Metropol or the Dresden State Operetta, and all the opera houses were represented. They auditioned us like a final examination and you received points for vocal material, style, personality and musicality, with a maximum of 25 points. You needed 21 points for an A-Theatre. If you were lucky, during the audition you received a message of interest from a theatre that said, ‘from summer onwards you’ll be singing this and that with us’.

I sang my exam there and had offers from Schwerin, Chemnitz and Gera as a mezzo-soprano. Actually, almost all the soloists were like that, because there weren’t that many – they were relatively strict in their choice of who was really suitable for the stage. But there were also very, very good choir graduates who then got solo positions at smaller venues.

There was not yet an influx of international singers. There were a few singers from the Eastern Bloc – Russian, Polish or Bulgarian. They were the ones who had a good command of the Italian school, because it wasn’t so common here in Germany. When you had your points and your job, you were on your way and earned your money. The fact that as an artist you had to be afraid of becoming unemployed was inconceivable in those days.

If you weren’t politically compliant, there could have been problems, but I never experienced that. But that was also due to the fact that I finished my studies in 1990, right at the fall of the GDR. I still received a scholarship from the GDR until 31 July 1990, and on 1 August I received my first salary in German marks.

The difference to the sports athletes, however, was that as an artist you weren’t allowed to travel. I would have liked to have been able to compete internationally as an artist as well. That was possible from January 1990, but I don’t think the system we have here now with agencies is healthy either. There are so many great singers in state theatres, but no critics go there, and if the singers are not in the right agency, they will never have a career. That was easier to do in GDR times.

There were already the opera studios, where young, especially dramatic voices were slowly built up and given time to develop. Today, the studios seem to be there to cover roles in-house for little money, but I don’t see the singers being developed properly. There used to be real plans – what do I do with a dramatic, young voice – what can it sing? How often can it sing? And the singer had to then be kept busy.

Did you feel that you had to be politically careful in those days?

I never had a problem with that. I studied in Weimar, and Weimar was a bit away from the big politics. In Berlin or Leipzig, it was certainly a bit more restrictive. I can remember a concert for the GDR’s birthday in 1989, and there was an orchestra composed of all four universities. They weren’t supposed to play in black and white, as usual, but in their blue uniforms, the ‘FDJ Blouse’, and they refused, because they said “we are musicians and the other orchestras wear black and white everywhere”.

As a result, the concert was cancelled and the next day there was an excellent review of the concert in the newspaper. Then came an order from the government and the Ministry of Culture to ex-matriculate all the musicians who had refused. I know that two universities did that, but in Weimar the vice chancellor didn’t do it.

You have been a fest singer in Darmstadt for over 25 years. What do you like about a permanent position and why did you want to stay in Darmstadt for so long?

Originally, I only wanted to be a guest performer in Darmstadt. But I auditioned and then they offered me a two year contract. Then I met my husband here and it made sense to stay here. Musically I am also at home here and in addition I was still able to perform a little bit as a guest.

The advantage is of course the fixed salary. No matter how you feel, how healthy or how ill, you have to pay your rent and health insurance every month. You go home every evening to your own bed, and you have permanent colleagues who you know very well. Whatever you have to say, the Darmstadt audience comes often and they love their ensemble. They can see how different the singers can be in different roles. That’s the exciting thing about our profession, that you can do anything – from opera to operetta to musical and through that you can find out what you are capable of. You can let all the ideas you have come up with come out on stage – I like that.

Nowadays I find it a pity that more and more is being specified. They say ‘I want a blonde mezzo’ or ‘black-haired mezzo’ and everything by type. In the past a mezzo was allowed to sing anything; she just had to put on a wig and play the type. Today, people are looking for a specific type already.

Can you choose which roles you perform?

No, it depends on your Fach1. I have a very good contract, which is specified exactly for dramatic soprano and everything else according to agreement and individuality. When I started, the lyrical mezzo was required to do everything from Handel coloratura to Rosenkavalier, simply everything. When you’re young, I think that’s quite good, because you don’t know yet where your strengths are.

Can you explain the Kammersängerin title for those who don’t know about it?

It is actually an honorary title, for which you have to be employed at a theatre for at least 15 years. It is for artistic achievement and merit in theatre.

You are also a spokesperson for the ensemble. What do you do in this role?

You are the link between the ensemble, the Operndirektor and the bosses. The ensemble is always small, so the lobby is not so strong, and there are things that affect not only you personally, but the organisation in general. I go there and complain on behalf of the ensemble! In the broadest sense I am a bit like the mum of the ensemble.

When you’re on stage, and especially with Wagner, where you get such a rich orchestral carpet rolled out for you, it’s like an escalator where you just have to get on and go with it.

What are the most important things that have changed during your career in the opera world?

These days everything goes faster and faster. The time for musical preparation for the ensemble has become much shorter. When I started in Gera, rehearsals were shorter on stage, but musically with the conductors much longer. We had at least six weeks time for them. You also had to sit and listen, even if you didn’t sing yourself, and see what happened in between, so that you knew what the music was like and how you could react. Then you went to the stage rehearsals, without the score. That made you much more secure and the staging work was much faster.

Is it more difficult for young singers now?

I think so, because the agents mostly don’t want to develop the singers at all. They simply want to earn money. They don’t care if they damage the singer with a role, because they have five others up their sleeve who could follow. In other words, they are not so obliged to be careful with the material that comes along. The theatrical landscape has changed somewhat, and there are much fewer theatres now. Financing is becoming more and more difficult and I’m afraid that only a few who have studied the profession will be able to continue their whole working life. If I want and can, I can sing until retirement.

With those who are young now, in their early 30s, you can already see that they are sometimes building up a second leg to stand on and are moving towards teaching, for example. Nowadays you simply have to assume that you won’t have this job for that long. And the older you get, especially in the female Fächer, such as lyric soprano or soubrette, the harder it becomes to work freelance at 40, unless you have already made a name for yourself. If not, you need a plan B.

What are the highlights of your career so far?

I would say when I sang the whole Ring within four days. I didn’t like Wagner at all – I was a big Verdi fan. And then, when you sing it once, you get so attached to the drug – it’s just so well written for the voice. It lies so well. Wagner was incredibly clever as a musician. As a person, I’m sure I wouldn’t have liked him, but I like what he wrote musically. When you’re on stage, and especially with Wagner, where you get such a rich orchestral carpet rolled out for you, it’s like an escalator where you just have to get on and go with it.

There are days when you go out and say ‘it’s cold today, it’s dark and it’s late’ – everyone goes home for the evening and you have to go to the theatre and work. But then when you hear the music, you get hooked again. If it goes well, if everything goes well, if your head is awake, your voice is awake and your colleagues give you the energy, then these are the magic moments. When we did the Ring here, it was such a great ensemble that I knew for ten years. It was really like a big family, so then you have evenings when you are really high.

Is there anything else you haven’t done yet that you would like to sing?

I always wanted to sing [the role of] Elektra [by Richard Strauss], or Clytemnestra. I like the roles where the character is broken, but not evil by nature, so I never wanted to sing Salome. She is too deliberately angry, but, for example, Abigail; there is a point when she learns that she is not the king’s daughter, but adopted, and that does something to her. Or Antigone in the Orff piece that we did here, where you would say that she is a completely normal person until the moment when she is told that she must not bury her brother. Then something happens.

And with Lady Macbeth too – she wants power, and then goes too far with the murdering. Clytemnestra is one of those, too, or Elektra, where she says ‘I always dig him up’. There is always a trigger with them, where they start running amok. So not evil from birth, but something happens, and then they are evil. They may be brutal, but you can understand why they went the way they did.

Nowadays it’s more about finding a niche for young singers where they are top. You have to find something where you can say ‘I’m better than the others’.

What advice do you have for young singers?

Hang in there! Be clever, listen to your own voice and see what it has to offer. Do not overdo it. Sometimes you have to go to the limit, and you have to go over it when rehearsing and practicing, to find out what the limit is. Where you notice, something is really painful, then that’s not the right way. If you feel a role in your stomach and you sing it without getting hoarse, then you should try it. If you have a good GMD2 or a good Studienleiter3 who says, let’s try that, do that, then you can take a chance.

It is important not to become too dependent on agents. Nowadays it’s more about finding a niche for young singers where they are top. You have to find something where you can say ‘I’m better than the others’. You have to serve your specialities, and young people should try and find the courage to develop these specialities. If you have a good agent who wants to develop you, they will go that way. And then, for maybe a few hundred euros less, you can go to a smaller house where you can try something special.

Getting rich is not the goal of opera singing. There are a handful of people who can do it, but I don’t know whether they are happy or not. Every note is worth so much money and the pressure they have from critics and the audience is immense. I think we do much better in the second or third tier and we don’t make worse art.

What do you need as a singer from a conductor?

I am someone who doesn’t look – I listen more to the orchestra. There are two or three operas in all my years where I have said that I would like to have a conductor. Otherwise I don’t need it, especially if the conductor is good. So I prefer to stay with the orchestra and you take the notes you need. I never wanted to be dependent on the monitors either!

You actually need a good conductor in the weeks before the stage rehearsals to try out tempi and to clarify breathing pauses and transitions so that it becomes organic. I expect and hope for a musical perspective from the conductor, where I get the feeling ‘ah, I haven’t sung Mozart like that yet. Then I’ll try it like this’. It is always important to try out what they want.

And from the stage director?

I expect more from the director. I expect them to know the play, to know the text, literally, even if they are foreign. They should have an idea of relationships and how to lead people. And to have the graciousness when they realise that they had an idea that doesn’t work; to admit it and not insist on it. It should not be a competition between director and actor, but a team that develops something together.

Sometimes I have seen directors who were really angry when an actor had a better idea. I want the role to work and the story to be told, and for the audience to understand it, even if it is Chinese. That even without surtitles, through the relationship between two people, through the energy on stage, you can see ‘oh, I think they like each other’ or ‘she’s about to take out the knife’ – you can see that in the energy. The director is like someone leading a game, someone who holds the thread and says ‘I’ll unravel this and let it go’. That is the art of a director, and you have a concept that has to be explained well to us. I don’t have to like it but I have to understand it, because if I understand it, I can present it.

I think the German theatre system is very good, and all foreign nations tell us that…but as is always said, if you live in paradise, you don’t always know that you live there.

What does the future hold for opera? Does something have to change, and as a German, do you feel a responsibility for the German system?

I think so. In the course of Corona you can see how many other countries are now saying ‘you Germans, protect your German cultural system!’ I think the German theatre system is very good, and all foreign nations tell us that. They say ‘my God, you have paradise here!’ But as is always said, if you live in paradise, you don’t always know that you live there. All those who have worked abroad and come back say ‘oh my God, how good it is here – we have to protect it’, especially the ensemble theatre.

I think we should get away from these guest contracts a bit more. You can afford it in large state theatres because they have a completely different number of visitors due to tourism. But if the German system must be preserved, then ensemble theatre is the way to go. It’s like a family and that’s what makes it so attractive. Buying guests – that’s not an art.

I would engage an ensemble for at least five years. Then the artists have time to say ‘this is my new home’, you have a GMD who develops a signature, and you have your opera family.

I hope that the ensemble theatre can stay. You are much more flexible as a theatre than if you only have guests. A theatre must retain its flexibility so that you can switch between things. I am totally against these supposed stars who are always on the move. Either they have six weeks to rehearse or I wouldn’t hire them!

Notes and Links

- Fach, (pl. Fächer) – Operatic singing roles in the German-speaking system are categorised using the ‘Fach’ system. Each Fach corresponds to a type of voice, and with it go certain roles. Examples of Fächer include Dramatic Soprano, Coloratura Soprano or Heldentenor.

- GMD – The Generalmusikdirektor, the chief conductor and music director of an opera house.

- Studienleiter – the person in charge of ensuring all singers in the opera house are musically prepared for their roles.

- You can read more about Katrin at her website here.

- At Staatstheater Darmstadt’s website, you can read about upcoming performances.