I got to know Australian-Italian tenor Aldo di Toro last year, while he was performing the role of Calaf in Puccini’s Turandot in Darmstadt. Born in Australia to Italian immigrants, Aldo studied at the Western Australian Conservatorium of Music and made his debut with West Australian Opera. After a long career down under, including singing regularly for Opera Australia at the Sydney Opera House, Aldo moved to Europe, where he had received encouragement at the start of his career from none other than Luciano Pavarotti.

Having sung in the UK and Italy, Aldo has now expanded his career into the German-speaking opera world. I sat down with him to discuss his career, and what it’s like to sing those big crowd-pleasing tenor arias.

For the German version of this interview, please click here.

The main thing in this opera world is to remain cheerful, crack a joke, and try to get on with everybody.

If you were not a singer, what would you have liked to do?

If I’d stayed in Australia I would have loved to have been a vet, because of the Australian wildlife. I was always around it while growing up on a farm, surrounded by wallabies, birds, reptiles, turtles. That was just my backyard, which was quite swampy! My favourite were the birds. Even now in Europe, I’m always looking at the eagles and the hawks when I go trekking in the mountains.

Do you have a favourite instrument?

The cello. It has a cantabile resonance close to the male voice. Jacqueline du Pre’s albums are still some of my favourites – the Haydn, Dvorak, and Faure. That sonority will always stay with me.

If you could have dinner with anyone from history, who would you choose?

My dad. He’s not around anymore.

Describe your Hot Toddy in three words.

I’ve got a ginger and lemon tea, thank you very much! I do like a bit of what the Italians call ‘caffé corretto’, in the winter above all, though not so much the grappa. The Italian punch is good – the abruzzo punch and fernet, Vecchia Romagna and all that kind of stuff. Anything that’s not too strong; the limoncellos or sambucas are the two more commercial ones. I also really like my white wine in summer.

Last year I lived Nessun Dorma for nine months, because I also did it in Magdeburg. I remember thinking, this is just a dream come true…It’s best to find the result within the character, not just to think ‘here comes the big piece’.

You’ve covered quite a broad range of the tenor repertoire so far in your career. How has your voice developed?

Since I’ve been working in Germany the repertoire has been heavier. The Germans want me to do dramatic Verdi and Puccini. There are lighter roles from these composers which I’ve been doing in the last ten years to build up to these heavier roles. I think starting out with Baroque music is a good idea – my debut was in Handel’s Alcina in Australia. At the conservatoire in Perth we had to do one Mozart every year, as well as chamber pieces and Baroque. I think that commercial opera, by which I mean those with orchestras of more than fifty instruments, should be left until later in the career.

A young singer getting close to their thirties can do it, but how long can they keep it up? Otherwise you get this boring scenario where singers come to rehearsals and mark. With that situation you’re not achieving anything. You have to come to rehearsals with the right vocal support.. the inner coil activated, the diaphragm. You have to be able to say, ‘okay I can get up then’, or ‘I can swivel around that door then’. Whatever the staging is, you have to sing in full voice at least at some points of the staging rehearsals. Concentrating on marking1 means you can’t concentrate on the score.

I actually started off in a natural vocal setting – in piano bars, musicals, and with some microphone work and jazz at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts. When I graduated I did supporting roles in operas, and then I stayed in bel canto after I left university for about 12 years. I kept away from verismo. I did my first Madame Butterfly only three years ago, my first real Tosca two years ago, and my first Turandot was last year. Sure, I’m not singing at the Met2, but these big theatres exist in Germany.

How do you see your voice developing in the future?

I would like to consolidate this work for the next few years. I never thought I would be singing roles like Calaf in Turandot – I was Nemorino! [from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore]. There’s time in a tenor’s life to build the strength, repertoire and experience and be really sure on stage. Then there’s a time to let the roles go, because they should be sung by 30-35 year olds! I do take into account how I’ll look on stage too and whether I’d look too old for the role.

A tenor often has the iconic arias and moments in opera. Do you ever feel pressure as a tenor that you’re carrying a performance, or that you have to deliver these big moments?

It’s certainly a popular repertoire. I definitely felt some pressure last year here debuting Calaf with Nessun Dorma in Turandot. We’re trying to open up for new audiences, and those audiences may not always have the full cultural background to understand all of what’s going on. But they know the tunes – maybe they’ve heard them on YouTube, or Pavarotti sang it, or they’ve seen it on Britain’s Got Talent. When they come along they’re waiting for that tune. So do you recognise that pressure, or do you stay in character and fill the journey or character arc? Absolutely the second!

And then you find yourself on stage and there’s smoke and lights coming down. When I did Nessun Dorma here I actually had to ask for less smoke! I’ve always taken it in my stride – try to remain cheerful and personable, even if I get frustrated when something isn’t clear to me. I don’t want to just sing it like it’s in concert form, but at the same time we are making music as well. In opera a result is achieved through repetition. It’s best to find the result within the character, not just to think ‘here comes the big piece’.

Saying that, there are sometimes moments when you know it’s coming, and you think of the soccer stadium. Last year I lived Nessun Dorma for nine months, because I also did it in Magdeburg. I remember thinking, this is just a dream come true. I remember a great historic Australian baritone who sang at Covent Garden called Robert Allman. In the Domain in Sydney I was visiting my mate there who was debuting Calaf, and in his dressing room was a note from Robert Oldman which said ‘welcome to the world of Turandot’.

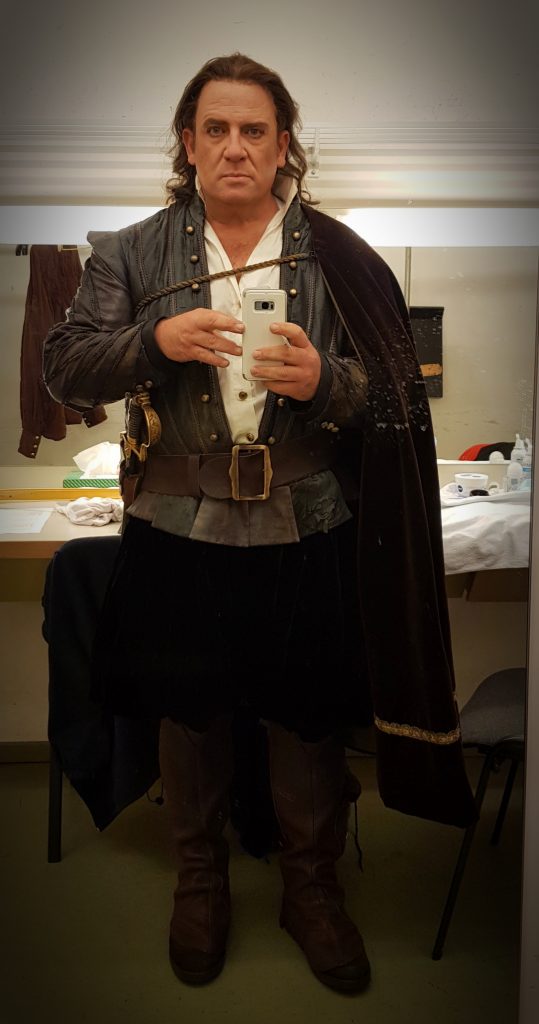

I remember thinking ‘wow’ last year, because it really is a world of its own. There must have been about 150 people involved. Backstage was one world, then on stage with smoke, mirrors and lights, costumes and makeup. Turandot was there wiping paint on me, which no one ever told me about, or if they had, I hadn’t understood the German! It’s really a gritty experience. It’s incredible that that particular role is the culmination of all the Puccini operas. And that carries you, with Nessun Dorma as the reward. The tough part is actually Act 1. By the time you start Act 3, it’s all yours. It’s hard not to think how popular an aria it is, but at the same time you have to serve it, kind of be the messenger.

[Pavarotti] was scheduled to sing one or two songs and we all had to sing one of his arias from one of his operas, plus something from our own countries. He pointed to my gut and said ‘good technique!’

How did you first get into opera?

I was born and brought up in Australia, but my parents were both Italian immigrants. Dad left as a young man to go and make some money and then come back and finish the house, the farmhouse that I live in now! Mum was much younger at 8, and her father was involved in agriculture. He then sent for the family to join him. My sister played the piano, and I’d sometimes look over her shoulder. At the weddings or parties, there were always the uncles singing everything at the top of their voices. The accordion would come out and there were tarantellas and mazurkas danced, so all of that European and Italian music was part of my life. I remember the beer keg in the corner being empty by midnight and then people standing around in groups of twenty deciding who could sing the loudest, all drunk by that point by the way! So out of that, it wasn’t strange for me to come out singing, but I was the only one to have any real musical training and I just loved it. I couldn’t see myself doing anything else.

Opera came really late. A maestro from La Scala3 would come down to Dad’s town Lanciano for his summer holidays and I would ask for lessons, bringing other Australian singers with me. In the year 2000, I received a scholarship from Opera Foundation Australia in Sydney to study at Bologna and after that, I decided to stay in Italy.

I won some roles and money here and there through competitions, and met people like Giuseppe di Stefano, who lived in Africa at the time, as well as Pavarotti in Moderna. We were in Sassuolo near Pavarotti’s town and he’d just got off the plane. He was scheduled to sing one or two songs and we all had to sing one of his arias from one of his operas, plus something from our own countries. He pointed to my gut and said ‘good technique!’

Since you’ve been in Europe, have you ever been tempted to go for a Fest4 position?

No. I wouldn’t last a month. Maybe because I’m a vagabond, and I’ve found a system that works for me. I’d rather travel in the middle of the night or the day before. I’ve already left a great life in Australia, but I think after a couple of months I’d get all of the things I don’t have now, like vocal problems. I thrive on the variety, the travelling, the freshness.

I feel like the opera companies aren’t really training the singers anymore. The singers who have good personal relationships and maybe have kids, seem to be the ones that are more content to do it. Singers have got to be happy. If a director can make a singer happy, he or she will give 100 per cent more, and the same with a conductor. I find if something isn’t working in a production, then suddenly all the weaknesses of the Fest system are exposed.

How does working in Germany compare to working in other countries like Australia or the UK?

So much more tax! I was really thrilled during my eight years working in the UK. I never lived there, but travelled there to work, with Opera North, Scottish Opera, Opera Holland Park. It was my language, and London became a home away from home. The UK never paid enough to warrant it financially. I would go as far as to say they are the worst paying in the world, and that was back when there was a lot of money flowing around.

Each country has its benefits. Life is expensive as a singer; there’s travel, there’s coachings. Expenses are being covered by the bosses less and less. If you want to work you have to be really flexible. For me Germany is close enough to Italy to be worth it. I also work in Austria and Switzerland so sometimes I even travel by car from Italy. The Australian scene is pretty lively. I did all the major cities and theatres and it’s well paid. I sang 12 seasons with Opera Australia at the Melbourne State Theatre and the Sydney Opera House.

Is it true that it’s actually a difficult venue for opera?

I love it! I remember singing there and feeling that we were in the audience’s laps. But then I’d go and listen to a performance and think ‘this orchestra sounds tinny’. So they might be right to criticise it, but I generally had a really good time there. There’s a saying, that when Melbourne State Theatre was created, that Australia finally had its international opera house. Pity that the outside’s in Sydney and the inside’s in Melbourne!

Can you tell me more about the opera festival that you run in Italy every summer?

It started by doing little concerts in the Piazza in one of our local towns with other friends, who all have other jobs – barbers, postmen, farmers or bankers. And then at night they’d bring out their instruments and play and sing. These friends were really good at it, and put on lively concerts. Then I slowly took over, and would come and sing Nessun Dorma, or O Sole Mio. Suddenly these concerts turned into an opera festival. We have local sponsors and are up to the stage now where we are putting on La traviata with the Abruzzo Symphony Orchestra this year, and they came last year for an opera gala.

We did Cavaliera Rusticana and Pagliacci one year and used all the stuff from the church. It’s amazing, because Cavaleria Rusticana was written by Mascagni in the late 1880s, based on Verga’s book. We found that under our 15th century church, we have these garments from the Bourbonic period, and the procession in the opera was literally from that period. So we had the real thing! Even the Jesus that was on the cross – it’s in the score! We have about 500 seats we can sell, and I sing every year.

What advice would you have for young singers now, particularly tenors?

I think younger tenors need to stay in Mozart and bel canto5 for as long as possible. Never stop exploring, but leave the big stuff for later. Stay young!

And the lifestyle?

Stay off the booze. It can be a hindrance. It’s fun, it’s sociable and it’s everywhere. But I’ve found out if you can determine when your down periods are and when your work periods are, then your work periods won’t last forever, and there’ll be plenty of time to have fun later. I think the booze really damages the voice.

The problem [in Germany] is that the Regie system in Germany tries to paint a picture rather than tell a story. It’s always about the visual rather than the interpersonal relationships.

What do you expect from a conductor?

I want to be a little bit afraid of a conductor. I want to learn – I want them to stretch me, but also have someone who is absolutely serene and calm. I want them to give me an environment that I can give all the different colours and needs of the score, so I think the conductor has to be stern and in control and call the shots when they have to. But they also have to give you space. If they’re clipping your wings all the time, just because they want to feel like they’re in control, or they have an idea of the score, then it’s not helpful, especially with the popular pieces.

When singers keep coming back to the score, the singer has to be as flexible as possible with the conductor. You have to hold our own ground because this is how physically you can sing the piece, but you have to let go of a lot of things. You choose your battles correctly. I need them to be steadfast, but also allow me to fly.

What do you expect from a director?

The problems now are with directors, whereas they used to be with conductors. You can appreciate the needs of a conductor, because they have fifty other elements to direct, so you can’t just do whatever you want. The conductor used to have all the power but about 15 years ago there was a shift in power. The problem here is that the Regie6 system in Germany tries to paint a picture rather than tell a story. It’s always about the visual rather than the interpersonal relationships. Likewise in that system the conductors have to take a step back, to the extent where the conductor just says they can come in after two weeks. That’s a problem, because for 15-20 days you have one guy or girl creating the nature of the work, the dynamics of the rehearsal room, but no one really strong enough to say, ‘hey there’s six bars there’, or ‘there’s a pianissimo there’, or ‘you can’t just do that’.

In Australia when I worked there, we would have four weeks of rehearsals with the conductor and director and the piece was created together in that time. Not a six week vague period, which is a colossal waste of time and resources. When you’ve got an intense period with everyone there, I truly believe you can do the whole process in thirty days. They’re starting to ask for a rehearsal period of seven weeks now for new productions.

The best quality in a director would be to really know the score. I’ve worked with some who only know the libretti! I need very specific choreography to know what to do with what phrase, and the intention. Give me a new take on it if you want; I don’t have to be traditionalist, but they have to work out whether they want that arc of the character to be natural or if they will intentionally break that up. I want the director to do his or her homework and expect to get results without us having to do repetition all the time. They need to tell me in clear terms what they expect from me. Within a structure of clarity we can be free.

A problem is that opera companies aren’t promoting the singers anymore; you used to be able to gain a following more easily.

What’s opera going to look like in 100 years?

I think we’re going to go back to a blank canvas because the money will dry up and the ones working there will be the ones that really want to be there. A problem is that opera companies aren’t promoting the singers anymore; you used to be able to gain a following more easily. All the publicity nowadays is usually an obscure poster in the middle of town somewhere that has some kind of artwork that has nothing to do with the piece, or maybe they’ve taken a photo of a handsome model! I think it’s going to become bare again, a blank canvas on which they’ll paint artwork. And then there’ll be a renaissance, with once again a concentration on quality.

I think generally opera will keep existing, and keep being relevant. I am disheartened by the lack of attention on the score. It’s always a battle between the visual and the musical. Someone has to give in, though when the production is beautiful and well thought out it’s a lot easier.

The main thing in this opera world is to remain cheerful, crack a joke, and try to get on with everybody. If something is really bad you have to say, but otherwise you’ve just got to get on and do it!

Notes

- Marking is a technique that singers can use where they do not sing with their full voice, but still make the words and melody clear with less voice. This means they do not have to keep singing with their full voice in what could be long and repetitive rehearsals.

- The Met is a common abbreviation for the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the most famous opera house in the USA. It is known for its very large auditorium.

- La Scala is the most famous opera house in Italy and perhaps the world, based in Milan.

- The Fest system is seen mainly in the German-speaking opera world, where a singer is able to have full-time employment in a theatre for a number of years.

- Bel canto is a style of operatic singing that was developed in the 17th-early 19th centuries. It is based on an exact control of the intensity of vocal tone, a demand for vocal agility and the clear articulation of notes and enunciation of words.

- The Regie system is a general name given to the style of directing that is seen in the German-speaking opera world. It often encourages more experimental and original types of staging than might be seen in other more traditional theatres.