This article is one of a series called ‘The Elton John Act’, which aim to demystify the process of becoming an operatic répétiteur and assist anyone wishing to audition as one in the German-speaking operatic system. Here we explore Mozart’s masterpiece, the finale of the second act of his opera Le Nozze di Figaro.

| Opera: | Le Nozze di Figaro |

| Composer: | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

| Length of Scene to learn: | Entire finale No. 16. Sometimes you will only be asked to play from Antonio’s entrance (bar 467-605) and then from the Allegro Assai to the end (bars 697-end). |

| Edition Used: | Bärenreiter in consultation with Peters (see below). |

| Recordings I listened to: | René Jacobs, 2004 (Harmonia Mundi), Georg Solti, 1982 (Decca), Carlo Maria Giulini, 1961 (Warner Classics), various versions on Youtube. |

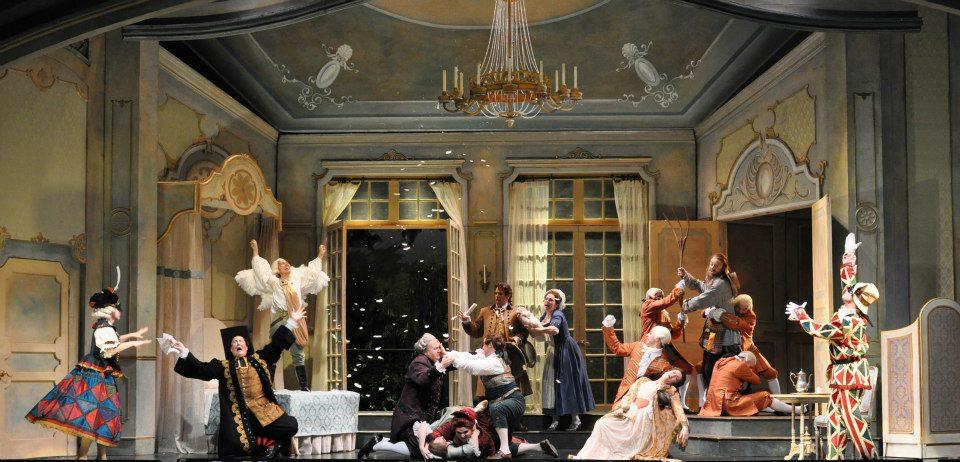

When I first thought I had an interest in opera, a friend of mine recommended I take part in an opera summer course in Weimar, Germany. The piece to perform was Mozart’s ‘Le Nozze di Figaro’. Having dutifully prepared the piano reduction to the best of my ability, I will never forget the first day of rehearsals, where we ran the finale of the second act. It was not unlike a rollercoaster, and though I fell off more than once, I realised I was hooked, and sat in awe watching my more experienced répétiteur colleagues navigate their way through the piece over the next few weeks. Having grown up knowing Mozart from his piano and choral music, it was like I had discovered a new and unexpected side to a well-loved friend.

Many experienced musicians argue that finale of Act 2 is some of Mozart’s best music, and it’s not hard to see why. Of all the excerpts that must usually be presented for répétiteur auditions, the characters here are the most well-defined, and due to the length of the extract, there is the greatest opportunity to show the maximum variety of colours and textures, as well as to demonstrate your interpretation and understanding of the style.

Like many pieces by well-known composers, you will find some people have very strict ideas that they like to preach, while other musicians place themselves on the complete opposite end of the spectrum.

Compared to the other extracts, I would say that the Mozart benefits the most from listening to a sample of recordings, firstly because many of the tempi are limited by what is possible for an orchestra to play, and secondly because it is so important to have an understanding of Mozart’s style. Too much pedal or too heavy a bass line can immediately obscure the phrasing or space in the texture that Mozart requires, and if you have limited knowledge of playing Mozart in other contexts, this can be difficult to get a sense of.

The excerpt is also so long, that listening to recordings will help you to begin to understand how every section links together. Watching a film version (there are many available on Youtube) will also help you to understand the many events taking place, and will help you to come to your own interpretation of the piece. Like many pieces by well-known composers, you will find some people have very strict ideas that they like to preach, while other musicians place themselves on the complete opposite end of the spectrum. I remember once hearing one person argue that the pulse should stay exactly the same throughout the whole finale, while in his book The Composer’s Advocate, conductor Erich Leinsdorf includes a very detailed analysis of the finale and argues for a much more subtle interpretation of interlinking tempi.

I used a similar technique when learning this excerpt as with Elektra, which is that I created a version of the accompaniment that I could play basically, as a guide to enable me to learn the vocal parts over the top. I then refined my playing in conjunction with my singing. As the only excerpt in Italian, it is crucial that your Italian is clear, and expressive, so as with Carmen, I would suggest studying with someone at the beginning of the learning process, and then getting them to listen to you singing at the end of your study too.

A word of warning for the piano part – it can be tempting to think that large swathes of the piano part are easy to play, and therefore to spend more of your time on Strauss for example, leaving Mozart to worry about later. While at first glance I would agree that the Mozart is easier to quickly get on its feet, in my opinion there is always much more work needed later on to refine my playing, and I always feel the most naked with this piece in an audition situation. Do not underestimate it!

For editions, there are two popular options. The Peters edition tends to be much easier to play, and has been written to fit a pianist’s hands better, whereas the Bärenreiter version as many areas that are un-pianistic, with lines that have to be excluded or rewritten in order to be playable. However, in my opinion the Bärenreiter retains more aspects of the orchestral writing, which I find more useful. Therefore I like to play from the Bärenreiter and consult the Peters for solutions wherever I run into a passage that I find unplayable or badly arranged for a pianist. Never be afraid to reallocate certain passages to a different hand than what is printed on the page or to miss out notes that are not so important if their inclusion means that something more important will suffer.

Just like at the beginning of the Smuggler’s Quintet, it is very important to establish your opening tempo correctly (especially if you have taken the interpretation that the whole excerpt must use the same basic tempo!). This is difficult, not only for all of the usual reasons (heart beating twice as fast as usual, nervous hands dripping with sweat, legs uncontrollably shaking etc.), but because finding the character of the irate Count, whose part we must begin to sing, means finding an uncontrolled aggressive character that feels at odds with cooly selecting a reliable tempo! Danger points for me where I am prone to rushing are also whenever there is a change of character, so make sure that the Countess’ opening lines are panicked but controlled, with Mozart’s piano dynamic helping you to achieve this.

The genius of this excerpt is that the music always expresses what the characters are feeling, even if they themselves are trying to hide it. Therefore at bar 13, the forte outbursts are clearly indicative of the Count’s rage, though it is important that your voice stays calm, as the Count himself is trying to refrain from one of his all-out tempers. He of course fails, and at bar 83, when he is threatening murder, you have a technical choice to make in the right hand.

In my experience, about half of répétiteurs attempt the thirds, though only a small percentage of them are able to execute them with a legato line that resembles how the orchestra would play them. I myself usually just play the upper line, though include the thirds where possible, which often tricks the ear into thinking there are more there than there actually are. (A teacher of mine once in fact told me to avoid all thirds and octaves in opera scores as they are too tricky, and will always be achieved at the expense of something more musical).

A definite weakness of the Bärenreiter edition is that barely any orchestral instruments are ever written in the piano part, though perhaps this could be viewed as an advantage, as it forces us to look in even more detail at the score. From the Molto Andante (often taken as eighth note = previous half note, by the way), my edition misses out all the orchestral articulation and also where the important horn texture differs from the rest of the wind passages. Make sure to have this written in and clearly differentiated in your playing, and then have fun practising singing Susanna’s triplets against the falling right hand sixteenth notes from bar 149.

As you get into the Allegro at bar 167, it is important to mention that it is important to actively find places to breathe. You really need a lot of stamina to get through this piece, and when I started to learn it (or when I return to it after a long time away) I have found myself feeling dizzy, because of how much I’m having to sing and concentrate on. Just as you would coach a singer, make sure you are taking appropriate breaths for the phrases you are singing, as otherwise it is here you will start feeling ill! This will also have the advantage that you are not tempted to rush a phrase because you are running out of breath.

When you begin to approach a passage with multiple singers, as in Carmen, be sure to map out exactly whose part you will sing so as to avoid any confusion.

It is always fun to spit out the flourishes in bar 177, which show the Count’s internal feelings of impatience, even though he is once again trying to remain calm in front of Susanna and the Countess. Through this section the arranger at Bärenreiter has often omitted some high woodwind lines that are worth putting back in, for example at bar 209-211 and 216-218. Make sure that the leaping chords at 212-215 are also more clearly voiced, as in the orchestra. After this, make sure that your sung upbeats are always correct and rhythmically accurate, because they are often written differently for each character. When you begin to approach passages with multiple singers, as in Carmen, be sure to map out exactly whose part you will sing so as to avoid any confusion. There is so much richness of character here that you can exploit as you alternate between the Count, Countess and Susanna.

Figaro’s G Major entrance at bar 328 is probably the easiest section of the finale to play, so as a result, make sure that it doesn’t begin to rush. Watch out here for details such as the longer quarter note bass note from bar 385 in comparison to the right hand eighth note. There is a lovely opportunity here to revel in the cunning of the Count with his ‘Con arte le carte convien qui scoprir’. The count begins his questioning in the following Andante section, which must remain crisp and light – avoid any temptation to use the pedal here, as the articulation must be crystal clear. I find Bärenreiter’s rendering of bars 420-422 unplayable, so rewrote them with the help of the Peters edition, prioritising the lower melody, which cleverly works in counterpoint to the Count.

In many auditions, if you are not asked to play from the very beginning, they will ask you to begin at bar 467, when the bumbling gardener Antonio enters the scene. This is because this section is fiendishly difficult technically, with bars 584-596 particularly thorny. My advice would be not to panic and to focus on playing what is important, always with an ear for what the orchestra sounds like. There are still many triplets in this passage where I miss out certain notes in order to make other things clear. When you do this, make sure you have written in where you are simplifying things, so that they are clear each time. In the frenzy of activity, sometimes phrasing can be lost, so ensure for example that the woodwind lines from bar 569 are always phrased away as an orchestra would.

The aforementioned bars 584-596 need particularly slow practise, and I worked slowly at first, singing while playing one hand only, then switching it around, then slowly putting it all together. Amongst all your own worries here, don’t forget Figaro’s pain as he pretends to hurt his foot with ‘e stravolto m’ho un nervo del piè!’ I often act this a bit and start sobbing, which actually fits quite well with the sense of relief I feel having got through this section!

Make sure you have defined each character and their motives as they sing, so that the drama is always clear.

In many auditions you will now be asked to skip to the Allegro Assai at bar 679, though prepare the intervening section well just in case. The Allegro Assai marks the beginning of the end. Whatever tempo you choose here, bear in mind that you need space for a quicker tempo at the Più Allegro at bar 783 and the Prestissimo at bar 907. At the beginning, keep your singing rhythmic, and I usually avoid playing the inner lines that double the singers in the Bärenreiter edition (eg. At bars 706-712). Here contrast is everything, as this passage can easily descend into a boisterous rush to the finish line. Make sure you have defined each character and their motives as they sing, so that the drama is always clear. You will feel like you are going mad, and certainly sound like it, but it will all be worth it when you get the job you wanted!

From the Più allegro (bar 783) it’s worth discussing some practicalities, which are important to sort out if we are to give our best. In the Bärenreiter edition, from here onwards there is one stave per page, so you’re going to have to plan your page turns exactly. This may include memorising certain bars towards the end of a page so that you don’t lose them with the panic of a turn. I find with these large staves, the text to sing is so far from the piano part that it is too difficult to read. From here to the end, I therefore wrote all the text just above the piano part, so that I don’t get sea-sick moving my head up and down like a crazy nodding dog. It is important that before the Presitissimo nothing gets quicker, so that you have just the right amount of space to put your foot on the gas here. As you get to the very end, I usually play bars 933-934 simply as arpeggios, because when the orchestra plays, the brass playing these is the most dominant sound that you hear.

When you get to the end, congratulations are in order. To play and sing this incredible scene is an amazing achievement, and hopefully you will feel confident to show off all the work you have done to an eager panel at your next audition!